In our current socio-political climate, the intersectionality of Blackness and feminism stands at the forefront of discourse and activism. To appreciate the power and influence of this intersectionality, we must explore the significant role Black women have played, and continue to play, in shaping social justice movements. The tireless labor and significant contributions of Black women often remain overlooked or undervalued. There is a disheartening gap in recognizing their contributions and addressing their unique struggles, and therefore indirectly the hardships of other marginalized groups. In our quest for justice and equality, it is crucial that we rectify this omission.

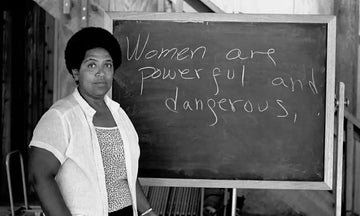

Photograph: Philip Cheung/The Guradian

The term 'intersectionality'—a critical component in the dialogue surrounding race, class, and gender—was first introduced into the lexicon of academic discourse by Kimberlé Crenshaw, a Black legal scholar, in 1989. Her seminal paper, "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics" (Crenshaw, 1989), sparked a transformative conversation that profoundly changed how we approach social justice and equality.

In this groundbreaking work, Crenshaw argued that traditional feminist and anti-racist discourses had failed to address the particular ways in which black women were made invisible by simultaneous and interacting systems of racial and gender prejudice. These intersecting prejudices created a unique form of oppression—known as misogynoir—experienced specifically by Black women.

Crenshaw's theory of intersectionality illuminated the profound impact of interlocking systems of oppression, positioning Black women in a dual bind where they are often doubly disadvantaged—victims of both systemic racism and gender-based discrimination. As a result, Black women often find themselves at the intersection of multiple sources of marginalization, experiencing a uniquely pervasive form of oppression that neither traditional feminist nor anti-racist discourses had fully acknowledged or addressed.

This critical concept has since become a cornerstone in contemporary feminist theory, unearthing the layers of prejudice experienced by Black women, and challenging previously held notions about discrimination. It emphasizes that Black women do not merely face racism and sexism separately, but they confront a complex, multi-layered oppression that combines these biases into a singular, intensified experience.

Intersectionality, as an analytical framework, has provided the necessary language to express the specific circumstances and challenges faced by Black women. It has created a dialogue that reveals the intricate relationships among various forms of oppression and continues to be an invaluable tool in our efforts to fully understand and dismantle these systems of oppression.

Black women have been formidable leaders in the fight for social justice, particularly during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. However, the narratives of significant figures like Rosa Parks and Ella Baker have often been oversimplified due to colorism and Respectability Politics.

In "At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance" (2010), Danielle L. McGuire counters the notion of Rosa Parks as merely a weary woman who refused to give up her bus seat. Instead, Parks is depicted as a strategic activist committed to advocating for victims of sexual violence against Black women.

Similarly, Ella Baker's substantial role in the movement, especially her leadership in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), has been largely understated. These examples underline the necessity of revisiting and correctly narrating the history of Black women's significant contributions to social justice movements.

As we move forward in time to the 1970s, the era witnessed an upsurge in the prominence of Black feminism, most notably with the establishment of groups such as the Combahee River Collective. This collective, named after the historic military campaign conducted by Harriet Tubman during the Civil War, was a groundbreaking Boston-based organization made up of Black feminists who were fervently dedicated to the struggle against all forms of oppression. The women of the Combahee River Collective deeply understood that their experiences were marked not only by gender bias but also by the intersections of racial and economic prejudices.

Their revolutionary commitment was aimed at combating the interconnected, multi-layered systems of oppression affecting their lives, including sexism, racism, classism, and heterosexism. These concepts were meticulously outlined in the Combahee River Collective Statement of 1977, a pioneering document that is widely recognized as one of the earliest and most comprehensive explorations of intersectionality.

The Combahee River Collective Statement underscored the collective's mission "to struggle against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression" and emphasized that their "politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters, and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and work."

This document, as much an articulation of the Collective's political agenda as a critique of the inadequacies of the larger feminist and Civil Rights movements, affirmed the need for a political movement that was conscious of and responsive to the multiplicative, layered nature of Black women's experiences. The work and activism of the Combahee River Collective remain a testament to the power and resilience of Black women in forging new pathways for social justice and equality.

Black women's activism remains a transformative force in the 21st century. The shift from feminism to womanism, with its heightened focus on the experiences and perspectives of Black women and other women of color, is pivotal to this modern discourse. An iconic example of this evolution is the Black Lives Matter movement. Conceived in response to rampant racial injustice, Black Lives Matter was founded by three Black women - Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi. Their collective passion and commitment, born out of personal experiences, have ignited a global crusade for racial justice.

Photograph: https://blacklivesmatter.com/herstory/

Garza, Cullors, and Tometi recount their experiences and the genesis of their movement in "When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir" (2017). This narrative invites readers into their personal journey of navigating systemic oppression and their relentless struggle for justice.

From the ashes of centuries-long discrimination, the trio rose to echo the voices of the voiceless. The formation of Black Lives Matter and its rapid global adoption exemplify the critical role Black women play in leading social justice movements. Moreover, it is essential to recognize that the BLM movement is not just about combatting racial prejudice but also intersectional discrimination that Black women face. Their work underscores the shift from feminism, which often overlooks the experiences of Black women, to womanism, which is inherently intersectional and inclusive.

The unflagging resolve of Black women in combating injustice is vividly showcased by the #MeToo movement, another crucial campaign founded by a Black woman - Tarana Burke. Burke's own harrowing encounter with sexual assault led her to create a movement that has echoed around the world. Her story, detailed in "Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement" (2021), serves as a beacon of courage, inspiring other victims of sexual harassment and assault to speak out.

Photograph: Brigitte Lacombe for Variety

Notwithstanding, it is vital to recognize the distinct adversities Black women face in their pursuit of justice. The concept of misogynoir, introduced by Audre Lorde in "Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches" (1984), encapsulates the unique prejudice of misogyny within racial justice movements and racism within feminist movements that Black women often face.

In addition to this intersectional bias, a myriad of systemic issues compound their struggles. The National Partnership for Women & Families (2021) reported that Black women encounter a wage gap, earning only 62 cents for every dollar that white, non-Hispanic men make. Health disparities are rampant, with the American Medical Association (2020) reporting a significantly higher maternal mortality rate for Black women. Furthermore, the Sentencing Project (2021) revealed a disproportionately high risk of police violence against Black women.

In the face of such marginalization, the resilience, voices, and perspectives of Black women have been instrumental in shaping and evolving feminist discourse. Renowned works by scholars like Bell Hooks, Angela Davis, and Audre Lorde, including "Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism" (1981) and "Women, Race, & Class" (1983), have been pivotal in challenging and transforming mainstream feminist ideology.

However, despite these efforts, a significant number of Black women felt that the term 'feminism' did not fully encompass their lived experiences that are uniquely defined by intersections of gender, race, and class. This gap led to the birth of 'womanism,' a term coined by Alice Walker. Womanism symbolizes a broader, more inclusive, and potent version of feminism, reflecting Walker's famous comparison - 'womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.' This sentiment implies that feminism, like lavender, can sometimes be a watered-down version of the rich, intersectional ethos embodied in womanism, which, like purple, radiates with a more robust strength and conviction in dismantling white supremacy and patriarchal oppression.

Photograph: https://freedomcenter.org/

The potency of Black womanhood - the intricate intersectionality of Blackness and womanism - forms a formidable resistance and catalyst for transformative social change. It is essential to recognize, appreciate, and honor the experiences of Black women who have been, and continue to be, the pioneers of social justice movements. Let their indomitable narratives fuel our collective battle for justice and equality. As we press forward, we must amplify the pivotal role Black women play in our society and ensure it receives the acknowledgment, visibility, and centrality it truly deserves.

Sources:

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. (1989). "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics."

- McGuire, Danielle L. (2010). "At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance."

- Combahee River Collective. (1977). "The Combahee River Collective Statement."

- Garza, Alicia., Cullors, Patrisse., & Tometi, Opal. (2017). "When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir."

- Burke, Tarana. (2021). "Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement."

- Lorde, Audre. (1984). "Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches."

- National Partnership for Women & Families. (2021). "America’s Women and the Wage Gap."

- American Medical Association. (2020). "Health Disparities in Black Women."

- The Sentencing Project. (2021). "Report on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System."

- Hooks, Bell. (1981). "Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism."

- Davis, Angela. (1983). "Women, Race, & Class."